Seashells

The marvel and peril of headphones

I can summon a voice, a melody, at a whim. I can run past a row of poplar trees while learning how the creation of pest-resistant wheat brought the 20th century agricultural revolution and saved millions of lives. I can cue up Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to soundtrack a Seattle summer sunset.1 Words and rhythms are delivered to my ears.

Our earliest ancestors would have gone mad at the notion of hosting foreign voices inside our heads. Who in their right mind would allow other voices into the sacredness of our consciousness?2

But for us, headphones have become a modern marvel. The portability of sound that emerged in the late 20th century transformed how we accessed information and art in a revolutionary way. We went from not being able to walk with sound, to listening through devices no larger than a cashew.

I spend a lot of time at cafés. It is the natural environment where my words emerge. My habit is to wear headphones while I work. Headphones keep me focused, they fixate my squirrely mind on the task at hand, reducing the source of my distractions by at least one sense. This scene is mirrored by about 80% of the people at the café. Neutral faces, the faint click-clack of the keyboards, some heads lightly bopping. We are all there, in our worlds of sound. We are all there, but not with each other.

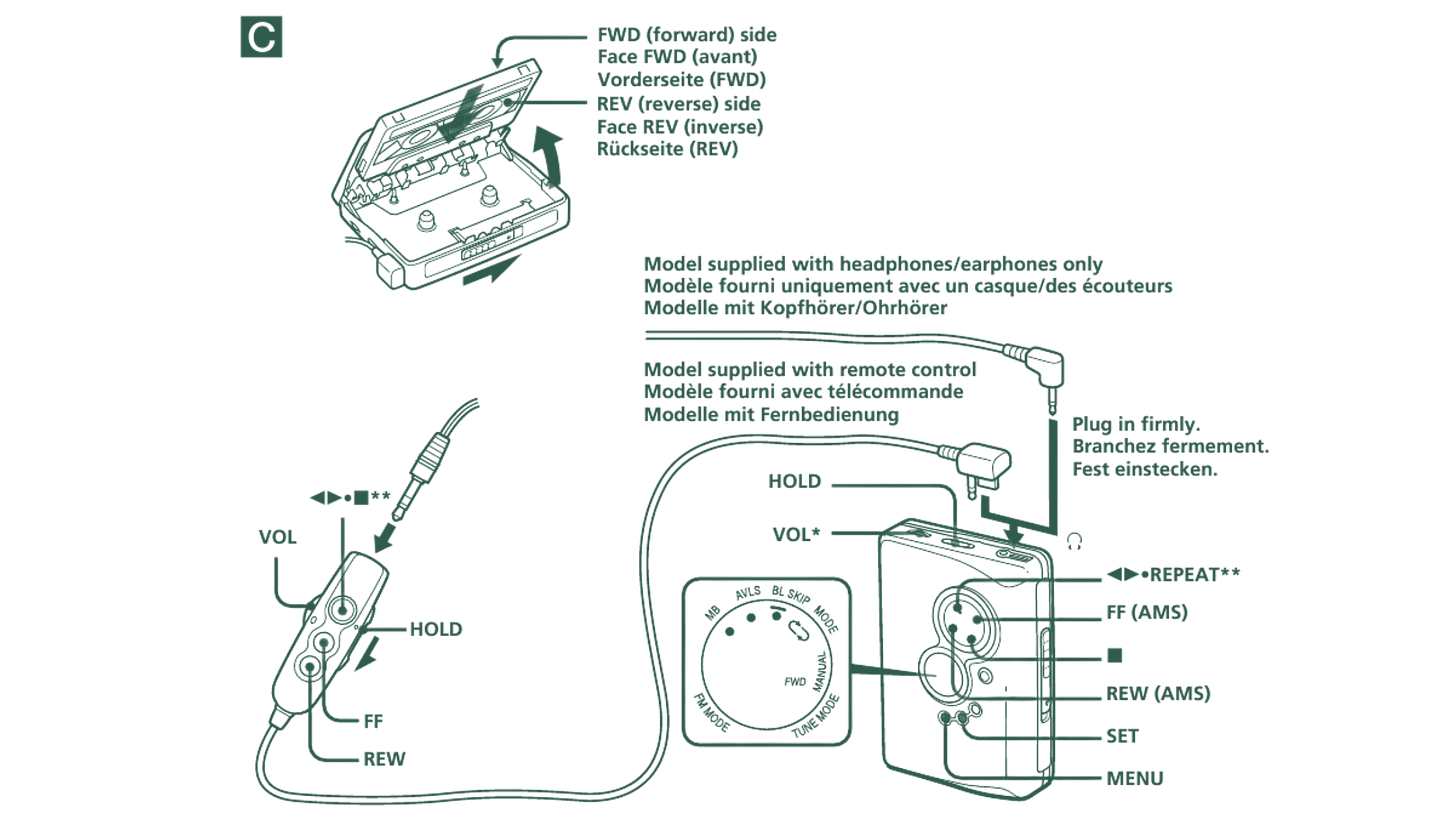

The Walkman Effect3

At the time the Sony Walkman came out in 1980, the youths were pretty excited about it. They could tune out the urban jungle and strut at the pace of Queen’s Another One Bites the Dust. To them, it ushered a new age of autonomy propelled by this artifact that became the “minimum, mobile, intelligent unit for music listening.”

Older generations didn’t have the same reaction. In one research study, young people were asked the following questions about the Walkman: are men with the Walkman human or not? are they losing contact with reality? are they psychotic or schizophrenic? This line of moralistic questioning was part of a broader trend whereby this new technology represented yet another way in which humanity was severing its relationship with not only the natural world, but also the world it had built.

It’s very interesting to see how radically our attitudes have shifted in the past 40 years. We’ve gone from questioning whether someone was schizophrenic to not batting an eye if half of the people we walk past have white p-shaped buds on the side of their heads. But perhaps as I’ve gotten older (*strikes invisible long white beard*) I have come to think that our relationship with headphones has become more sinister than intended.

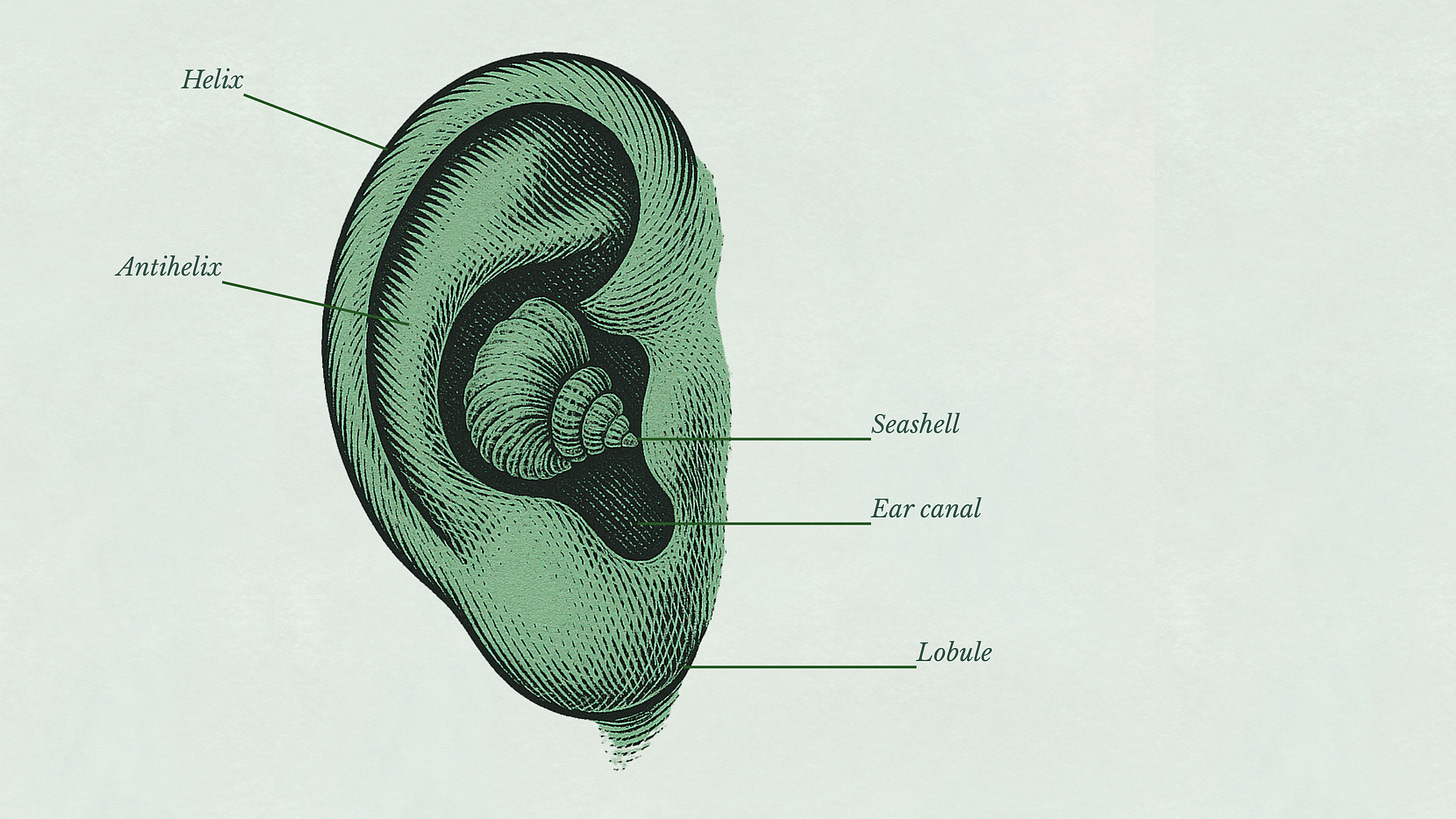

Becoming Mildred

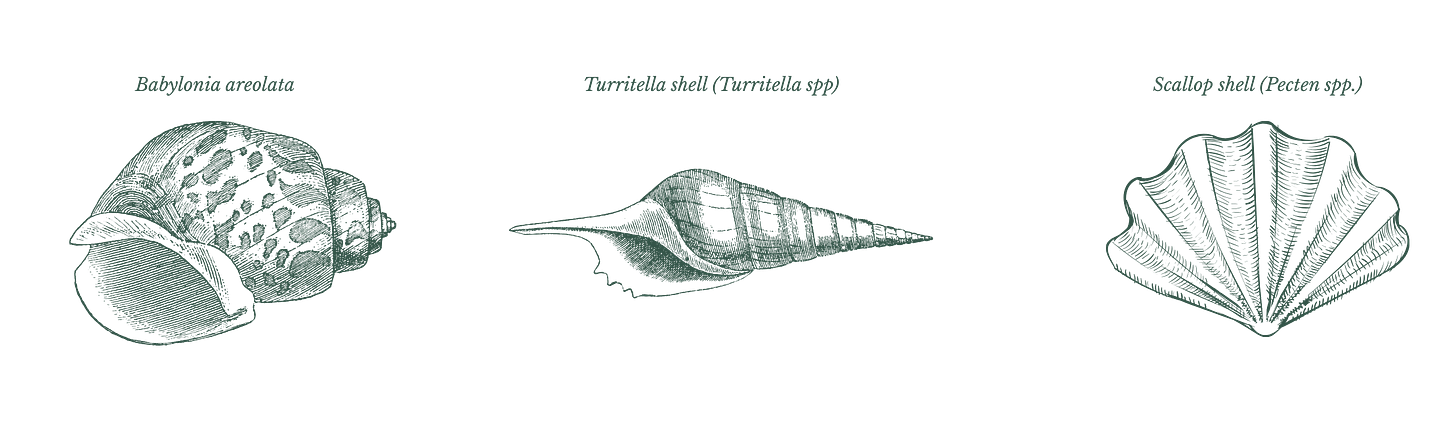

In 1953, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 was published. The book describes a dystopian world where firefighters don’t fight fire, but rather create it to burn books, where censorship is omnipresent, an interactive TV the size of a living room wall is entertainment, and citizens wear “little seashells” on their ears. As the book describes, these seashells bring “an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talk coming in, coming in on the shore of her unsleeping mind.”

One of the key conflicts in the book is between the main character, Montag, and his wife, Mildred. Mildred never removes these seashells from her ears, and in between listening to the government propaganda and interacting with the big interactive TV, she becomes disconnected from any romantic relationship with Montag and too distracted by the sounds and sights being fed to her to question the status quo.

While reading the book, any mention of the seashells triggered a sinking guilt. I didn’t have to use headphones—seashells—as obsessively as Mildred to understand what Bradbury was hinting: seashells symbolize the ways technology can bewitch us into a separate parallel reality that, in turn, severs us from the physical world and human relationships.

I fear we are becoming Mildreds. Unable to experience the world without seashells on our ear, our attention increasingly captured by what we hear. And the consequence of our indulgence in auditory isolation is a deepening sense of isolation and an inability to experience stillness.

“What? I can’t hear you.”

Headphones have become a de facto do not disturb sign. That’s how I used them back when I had a desk job, that’s how I used them in public spaces, and that’s how at least 50% of people reading this use them. They are the equivalent of retreating into a turtle shell.

The problem with using headphones to shut out the world is that, in an era of increased anti-social behavior, we are further shutting off any opportunities to converse and connect with others. We are already having problems, worldwide, developing friendships4 or even “weak ties.”5 Even in scenarios where you interrupt someone wearing headphones, the tendency is to be apologetic, as if talking to someone with headphones is the equivalent of bumping into them. And since people are spending less time socializing6 and more time in their own homes, this precious time in public—a time ripe to expand our zone of serendipity, gets drowned out by our desire to listen to Dua Lipa (again).7

Aversion to Silence

Headphones also feed our brains with constant auditory stimuli to the point of gluttony. I struggle to undertake any monotone task without a beat to help me get through them. As much as I may want to experience a cinematic moment by pairing it with a soundtrack, what this ends up creating is a pattern where noise becomes more valuable than silence.

This goes completely against one of the major revelations in the past few years: the power of silence and boredom as conduits for creative ideas and regulation of our nervous system.

My addiction to noise, then, becomes a self-defeating palliative that gets in the way of experiencing moments of discovery.

What am I hiding from?

A couple of days ago, I went to a nearby park to read. I would usually wear headphones while reading outside, but given my reflection on the downsides of headphones, I kept the seashells in my pocket. I wanted to be present, to rawdog reality.8

Ten minutes in, a middle-aged lady approached me. She asked me if there was a karaoke place nearby. “I’m not sure. Maybe close to Main Street,” I answered.

She replied, in one breath:

“Ah ok. Sorry to disturb you, I know you are reading. It’s just I was supposed to go to karaoke with this guy I’ve been seeing, but that’s not happening anymore. We are not together anymore. It turns out he has a brain tumor and he’s just very erratic and so we are not dating anymore…my friend who is a property manager told me she also dated someone like that…you have to give them space and time. Maybe I’ll get back together with him. Sorry to disturb you. But anyways, I don’t have a phone because my last one died and I went to the store and they told me it would take four months to replace the battery. And I don’t drive so I don’t want to go to the Lime [karaoke place] because it’s scary to take the bus at night…I was supposed to go to karaoke with this guy but now we are not together. I’m [redacted], what’s your name?”

I gave her my name and did everything humanly possible to gently steer the conversation to a sudden conclusion that would allow me to not get sucked into this woman’s soap opera.

Then, I reached into my pocket for my earbuds.9

This random lady telling me about her drama is exactly the scenario I seek to avoid by using headphones. I use them as protection from uncomfortable social interactions.

Something’s got to give, though, if I want to feel more connected with the world, more comfortable engaging with strangers. I don’t think it’s realistic, or practical, for me to stop using headphones altogether. But there’s probably a sweet spot between this end of the spectrum and wearing them all the time like prosthetics.10

I have to risk enduring, and starting, awkward and weird conversations. I want to be aware of when I’m using sounds to avoid silence. I want to remind myself that, yes, headphones do allow me to create my own reality, but that in the process I shut off others who may be interested in being part of mine.

Technology delivers value through optimization and convenience. The promise to make life easier, less friction, less effort. But as I’ve observed with my use of headphones, convenience comes at a cost, and on that side of the ledger are the things we yearn for the most: connection, stillness, and presence.

What we really want to experience tends to happen away from the gifts of technology, not because of them.

Seattle has the best summers in the United States. I won’t argue about this.

Caveat: Plant medicine and a bunch of other ways people got high. But I digress.

The term “The Walkman Effect” was coined by Shuhei Hosokawa in an essay by the same title. Quotes in the next couple of paragraphs come from this essay.

If you are struggling with forming friendships, this piece by Beck Isjwara can help.

Weak ties refers to a term coined by sociologist Mark Granovetter. It is defined as “casual connections and loose acquaintances,” which Granovetter argues that weak ties provide advantages in scenarios like getting a job.

From Derek Thompson’s Anti-Social Century: “Between that year and the end of the 20th century, in-person socializing slowly declined. From 2003 to 2023, it plunged by more than 20 percent, according to the American Time Use Survey, an annual study conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.”

I wrote this sentence in the royal “we,” but I really mean just me.

Rawdogging…ok, how do I explain it for an audience that includes my Mom? Well, rawdogging is simply doing things without using technology. For instance, going an entire plane ride without watching a movie or using your phone or any digital stimuli. Yes, let’s just define it like this.

She still approached me a couple of times to ask me again where the closest karaoke place was, and then to ask for the time since she doesn’t have a phone.

In one of the cafés I frequent, a couple of the baristas tend to be wearing headphones while taking my order at the register. The sensation I get from this interaction is fractured, as if I’m a nuisance, not a customer.

I very much enjoyed this essay, but I too was thrown off by the karaoke lady!

I was really hoping you’d say you took her there yourself. And where I’m coming from, is following the lead of strangers and derailing my plans for them has led to some of the best turning points of my life… but at minimum at least an interesting story. Maybe next time?

Plot twist...I thought the interaction with then karaoke woman was going to a special moment of serendipity you were thankful for, that you would've missed with your headphones in. Not where I expected things to go!

I'm torn on this. Sometimes I feel guilty for having headphones in too much (ex: I've been on the streets of China and realize that I'd rather be soaking in the unique environment around me rather than listening to whatever I'm listening to). But at the same time...man they boost the quality of my life, every single day. I love having headphones. I guess I trust myself enough to take them out when I get a gut feeling to do so (elevators would be another example, I prefer to unplug and say a quick hello to other people in the elevator). But maybe I could unplug a bit more than I already do