Abundance — A Book Report

Liberalism that builds

As a kid, there were three answers for what I wanted to be when I grew up: Soccer player for Real Madrid, radio journalist, and President of Colombia.1

I used to record myself "speaking English" (by appending -tion to words) and report fictional world news. Throughout my teens, I mentally crafted presidential speeches—imagining how to end Colombia's civil war, lift us from poverty, and build a thriving nation. I'm a political person at heart.

I've kept politics mostly off this newsletter, partly to avoid alienating subscribers, but mainly because I know political views mainly change through lived experiences, not blog posts. I’m hesitant to oversimplify complex issues or contribute to the erosion of political discourse. Growing up in Colombia taught me this: when meaningful discourse erodes, violence becomes the loudest voice.

However, I'm making an exception for the book "Abundance." If you expected something about the law of attraction—I love where your head's at, but that's not what I’m writing about today.

Still with me? Let's dive into the latest liberal manifesto that's infuriating both progressives and conservatives.2

What’s the book about?

It’s a book that offers a progressive political vision focused on building more housing, energy, transportation, and healthcare while removing bureaucratic barriers to innovation and growth.

The book’s thesis is clear: The future we want lies beyond the horizon of what we're willing to build and invent.

If we want a future with affordable housing, clear skies, no cancer victims, and free-ninety-nine electricity—well, you have to build and invent that reality. You can’t just manifest it.

The book is written by Ezra Klein, columnist at The New York Times, and Derek Thompson, reporter at The Atlantic. Derek is one of my favorite writers, most recently having written this incredible cover story for The Atlantic exploring our growing social isolation. His writing style—witty, insightful, and substantive—represents the kind of writing I aspire to consistently create.

The authors deliberately mention this book is written for a liberal and centrist audience. It serves as an intervention for progressives and Democratic leadership—a wake-up call to reconsider our relationship with government, question our reflexive defense of bureaucracy, and propose a shift from political performance toward delivering real improvements.

It examines four areas needing abundance: housing, transportation, healthcare, and energy. Ezra and Derek show government's vital role in driving innovation (through the Clean Air Act, DARPA, Operation Warp Speed), while revealing how excessive oversight and litigiousness have stifled progress and eroded public trust in government.

These are the ideas that resonated the most with me:

1. Subsidies don’t solve supply issues

The book makes the argument that progressive policies which have sought to subsidize things like healthcare (Affordable Care Act) and education (Pell Grants) are good. However, it faults the left for not considering that, eventually, you need more of what is being demanded if you are serious about the long-term affordability of these foundational elements of our social contract.

Consider Kamala Harris’ campaign proposal to give first-time home buyers $25,000 in down payment assistance. The sum seems generous, but in supply-constrained housing markets, that’s just going to drive up the cost of the available housing by a similar amount.3

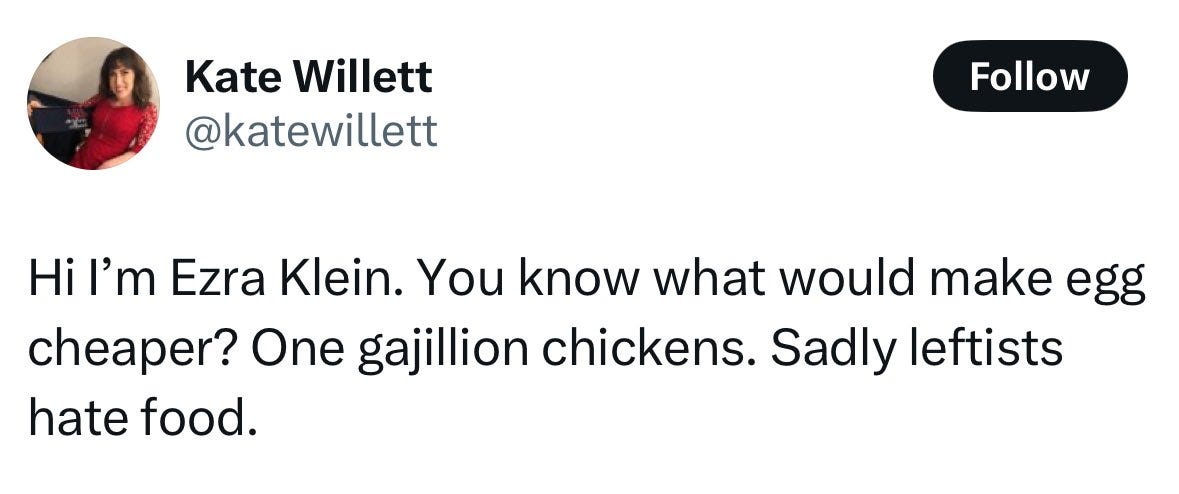

This mocking tweet actually captures the position perfectly.

2. Abundance is more constructive and effective than scarcity

The book examines the “degrowth” movement that has gained traction in Europe and parts of the US. It challenges the movement's central claim that resolving problems like climate change and inequality requires developed economies to contract and developing economies to grow more slowly.

Logically, this would result in lower emissions and perhaps greater availability of valuable resources. The problem is that it is not only impractical, but completely unrealistic. Basic game theory tells us that if players don't trust each other, they will optimize for their own outcomes. Also, humans are naturally motivated by loss aversion, which is why removing things is always harder than adding things.

The book goes on to warn that the butterfly effect of the degrowth agenda is how it creates opportunities for authoritarian governments and strongmen to gain power by promising the opposite of degrowth policies—ultimately making our problems worse.

3. Government as wings, not dead weight

This is probably the main point of the book's second half. It explores how penicillin wouldn't have existed at the scale that it did without government involvement. The United States was making exceptional progress on solar energy in the early 80s until the Reagan administration withdrew funding, making it unprofitable for innovative solar companies to continue their work.

I think the metaphor of government as wings is apt: it is not the whole vehicle, but you need it for lift, to stay afloat, and to maneuver.

To enable government to function as a productive set of wings, the authors advocate for a combination of push-pull funding.

Push funding occurs when the government invests money up-front to incentivize invention (like NIH grants). Pull funding happens when the government rewards innovation breakthroughs after they occur (like reimbursements to COVID test manufacturers).

An abundance-pilled government would strategically use both mechanisms to make aggressive bets on scientific breakthroughs. The book also argues that the current grant-making process is broken, focusing on too many safe bets and transforming scientists into grant administrators rather than innovators.

4. “It’s housing, stupid”

If I could buy a billboard in Downtown Seattle, it would say: “It’s housing, stupid.”4

I’ll reserve the why for a future essay, but I’ll give you the punchline: Our affordability crisis is directly tied to the cost of housing. It may not be the biggest component, but it is the phantom thread.

I was glad that the book covered it pretty effectively. It offers a damning assessment as to why cities like San Francisco have stifled any new construction through permitting gimmicks and bureaucratic banana peels.

It articulates what I see as the fundamental contradiction in American housing policy: Americans have grown up with the idea of a house as a wealth-building vehicle.5

As a result, any effort that might negatively impact this wealth-building asset is perceived as contrary to homeowners' self-interest. This explains why NIMBYs often claim they DO want more affordable housing—just not in their backyards.

From the book: "How do we ensure that housing is both appreciating in value for homeowners but cheap enough for all would-be homeowners to buy in? We can't."

5. Invention relies on implementation

This was probably my favorite idea from the book. Derek talks about “The Eureka Myth,” the idea that, as a society, we mythologize the moment of discovery (Newton’s Apple, Edison’s lightbulb experiments, and Archimedes’ OG “Eureka!” moment), but what really matters is how “individuals and institutions take an idea from one to 1 billion.”6

The authors use the miraculous story of penicillin to illustrate this point. The initial discovery of penicillin is so remarkable that it sounds like an urban legend (I won't spoil it for you). However, the book emphasizes that penicillin only became widely available because the Office of Scientific Research Development, a government agency established during WWII, funded crucial research to stabilize large-scale production and financed manufacturing facilities. This government intervention led to the exponential growth in penicillin production "from an average of 10 million units per plant per month in 1942 to 646 million units by June 1945."

We can see similar impact with the NIH, an agency recently targeted for bushwhacking budget cuts. Recent data shows that NIH-funded research contributed to 354 out of 356 drugs approved by the FDA between 2010 and 2019. Despite criticism from certain tech figures, the NIH remains one of the world's most important innovation engines.7

However, the book is not without its flaws and here are the two big ones that I’m having a hard time ignoring.

Ok, but what about education and public safety?

The book makes no mention of education and public safety. I mean, those are pretty important things for a society.

If Democrats' focus on process over outcomes in housing and transportation has eroded faith in government, education and safety have surely done the same.

Public education’s failure diagnosis is accepted across the political spectrum, but the proposed solutions diverge dramatically (give it more money versus blow it all up). Add the cultural debates about teaching children about gender and race, and the contested boundary between education and indoctrination, and you have a thorny issue that deserved attention in this book.

Public safety presents similar thorniness. While xenophobia exaggerates immigrant crime rates,8 cities like Seattle have become too permissive of anti-social behavior. Trump's gains in major cities likely stemmed from safety perceptions, despite improving national crime statistics9—a "vibecession" of public safety.10

Where do education and public safety fit within the Abundance agenda?

Will this change anything?

My biggest criticism: I don’t think the book will change many liberal minds. The book assumes that by speaking heart-to-heart with liberals, using the common language of technocracy and appealing to moral good will motivate new attitudes around government and policies that encourages growth.

It paints a solarpunk future without explaining the consequences of maintaining the status quo. This is change management 101: you have to make the consequences of doing nothing visceral and clear—make your audience believe that they are on the Titanic.

Why should a homeowner in Queen Anne, a residential neighborhood next to downtown Seattle, be willing to accept condos next door? What happens if they don’t?

Most "doom and gloom" messaging from the left focuses on authoritarianism and institutional collapse. These warnings contain truth. Yet the affluent liberals whom this book targets often have the economic resources and social mobility to weather political turbulence.

If things get bad enough, they'll simply move to Portugal and retire.

But what about those who remain here—a Gen Z generation seemingly growing up with a brain-eating amoeba attached to their hands, uncertain about what employment will look like in five years, or elderly boomers who lack the privilege of becoming gringos in Lisbon?

An Abundant Future

I'm glad this book exists—it captures many of my political beliefs. Government shouldn't be omnipresent, but it can be tremendously helpful. I've never embraced the Libertarian minimal-government utopia, having seen how ungoverned areas in Colombia become desolate and fall under the control of warlords. Americans might say, "That would never happen here," yet daily the US increasingly resembles Colombia.

Honestly, I don't think most Americans understand how effective their government is relative to other countries. Yet, the liberals who too easily brand critics as heretics or fascists for questioning whether government is fulfilling its purpose aren't helping restore faith in our institutions.

This is the main message I take from the book: The future we want must be built, not merely imagined—by optimists who see system imperfections and, instead of accepting the status quo, march toward an abundant future for everyone.

For a brief period I wanted to be Pokemon master, but to my still present disappointment, Pokemon are not real.

For the purposes of this piece when I use the term liberal, I mean social liberal, which is different than classical liberalism.

VP Harris did propose things that would help on the supply-side, but the contention I have, and that the authors would as well, is that you can say at the federal level you want to build 3 million new homes during your term, but if local governments, which really hold the power in a lot of the zoning and permitting requirements, won’t budge, the President can’t make houses appear out of thin air.

This is a callback to the phrase coined by political strategist James Carville in 1992 where he was talking about Bill Clinton’s messaging strategy. The original phrase is “The economy, stupid.”

I actually think this applies to many countries in the world, especially those that have large rent-seeking economies. But I am trying to keep the focus of this piece US-centric.

The Eureka Myth appears in this essay Derek wrote for The Atlantic.

Tweet offering this conclusion (I went to the report they cited this from and it tracks).

This report from the Libertarian-leaning Cato institute talks about possible reasons for why immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants may commit less crime and links to other studies.

The book mentions how LA county shifted eleven points towards the GOP, along with similar shifts in Detroit, Chicago, and New York (p.18)

Credit to Kyla Scanlon for the term. You can read her post here.

The image of you practicing to be president of columbia is actually moving and inspiring to me. But in the article itself you've done an excellent job of exposing me to some new and useful ideas, and your review of the book seems insightful and informed. We're in Canada as you know and all the same issues are brewing, as they are worldwide I guess.

I usually stray away from reading about politics but you piqued my interest to keep reading. So succinct Camilo. Job well done. 👏

My favorite part was your perspective at the end of course :)

Next up, I’d love to read more about how “daily the US increasingly resembles Colombia.”